Development

Development

Development is the first stage of the filmmaking process and includes coming up with your idea, writing the script, and figuring out how to pay for everything you want to do.

We’ve curated some resources for you on this page to help get you started. Use them as much or as sparingly as you’d like. Find a way that works for you and your team — and have fun!

story archetypes

If you’re thinking about your film and panicking because you have no idea how to build the story, take some comfort in the fact that “everything is a remix.” According to filmmaker Jim Jarmusch, “Nothing is original. Steal from anywhere that resonates with inspiration or fuels your imagination … Authenticity is invaluable; originality is non-existent. And don’t bother concealing your thievery — celebrate it if you feel like it.”

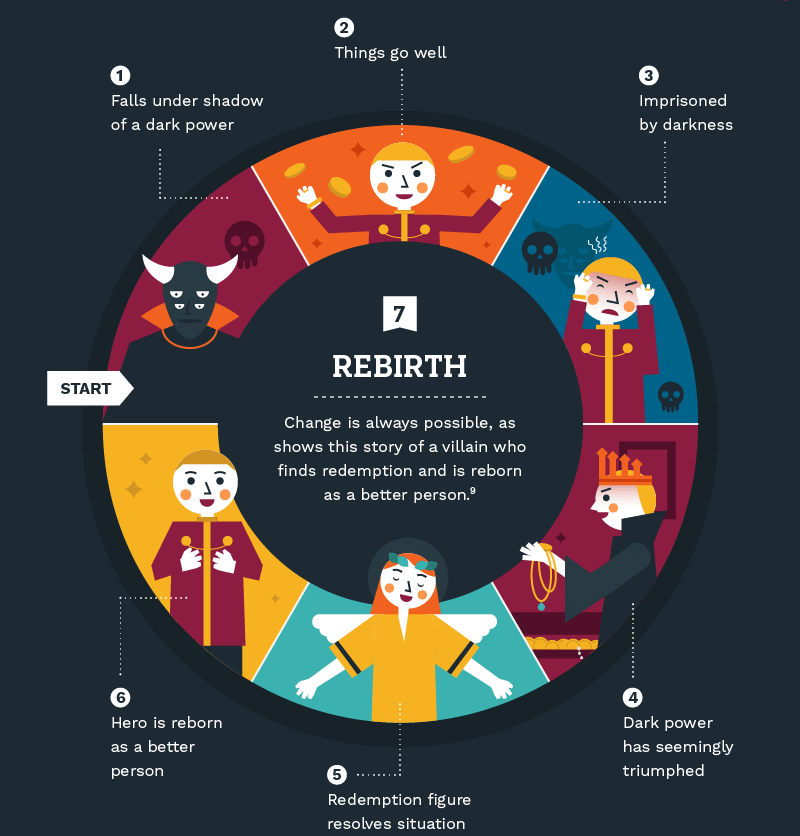

In his book The 7 Basic Plots, Christopher Booker finds patterns in the stories we’ve told throughout history and have boiled down human storytelling into some core patterns, or archetypes. Once you learn his 7 archetypes, you will start seeing them everywhere and they can be a great tool for getting started…

7 Basic Plots graphics made by Louder Design

graphing stories

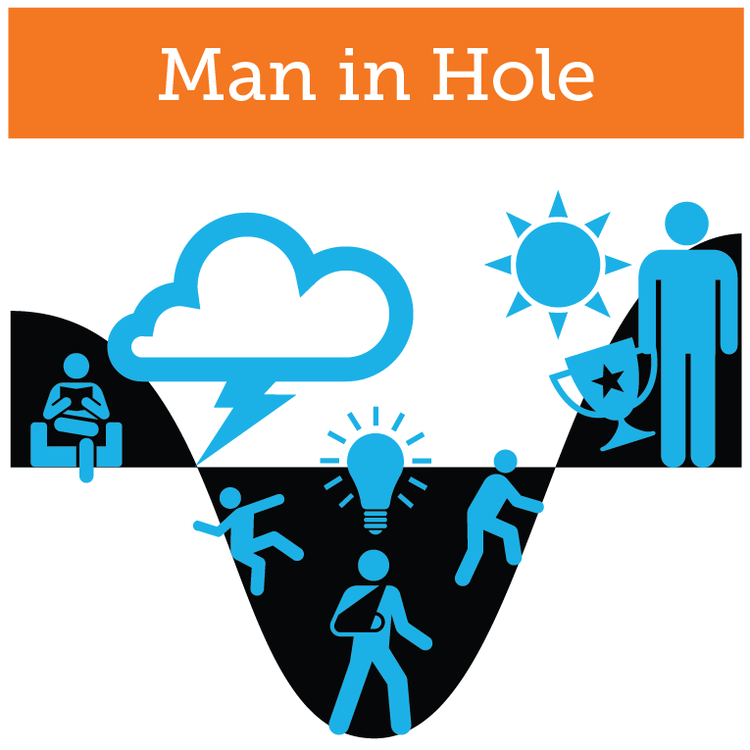

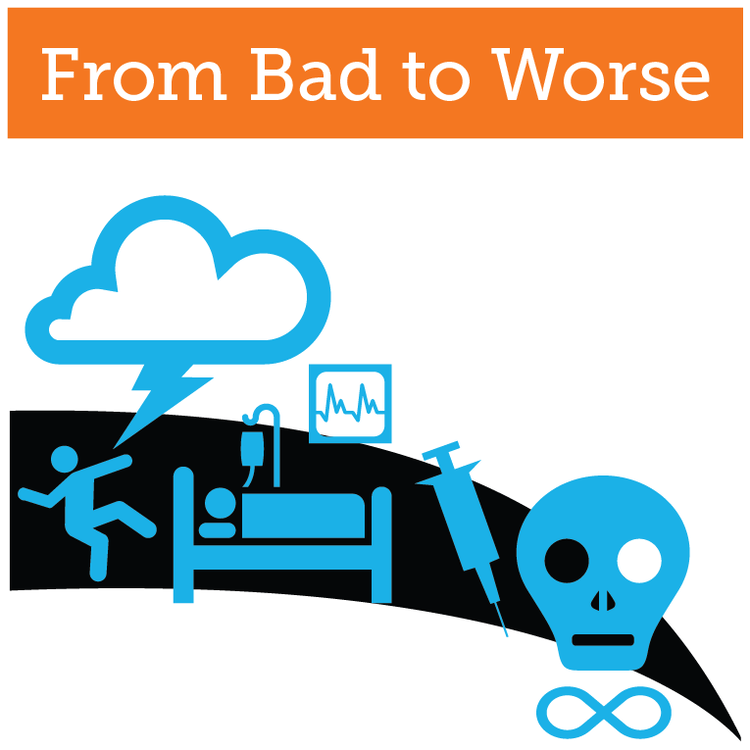

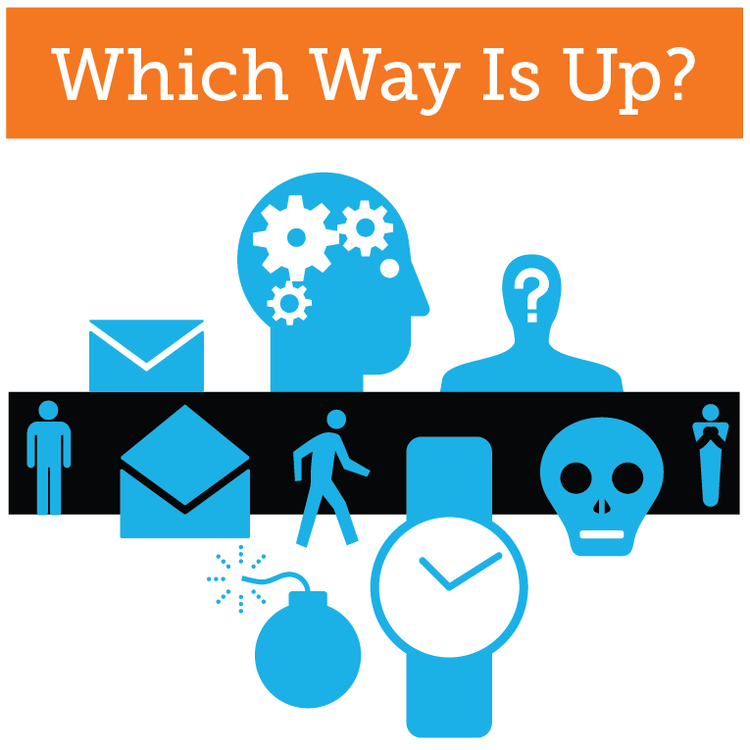

Another way to visualize your story is by graphing its shape Kurt Vonnegut-style. The author of Slaughterhouse-Five and Cat’s Cradle came up with a simple approach. His system involves two axes: the X-axis the beginning, middle, and end of the story; and the Y-axis represents the main character’s good or bad fortune. As an exercise, it might be useful to graph some of your favorite plots, to generate a story from a graph, or build a story by one of the graphs below:

The main character gets into trouble then gets out of it again and ends up better off for the experience.

Examples:

Arsenic and Old Lace

Harold & Kumar Go To White Castle

In many cultures’ creation stories, humankind receives incremental gifts from a deity. First major staples like the earth and sky, then smaller things like sparrows and cell phones. Not a common shape for Western stories, however.

The main character comes across something wonderful, gets it, loses it, then gets it back forever.

Examples:

Jane Eyre

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind

Humankind receives incremental gifts from a deity, but is suddenly ousted from good standing in a fall of enormous proportions.

Example:

Great Expectations with original ending

The main character starts off poorly then gets continually worse with no hope for improvement.

Examples:

The Metamorphosis

The Twilight Zone

Humankind receives incremental gifts from a deity, is suddenly ousted from good standing, but then receives off-the-charts bliss.

Example:

Great Expectations with revised ending

The story has a lifelike ambiguity that keeps us from knowing if new developments are good or bad.

Examples:

Hamlet

The Sopranos

It was the similarity between the shapes of Cinderella and the New Testament that thrilled Vonnegut for the first time in 1947 and then over the course of his life as he continued to write essays and give lectures on the shapes of stories.

““I believe that reading and writing are the most nourishing forms of meditation anyone has so far found. By reading the writings of the most interesting minds in history, we meditate with our own minds and theirs as well. This to me is a miracle.” ”

Text and graphics made by Maya from Tender Human

where can i read screenplays?

You may want to find inspiration by reading screenplays or learning more about them. The Internet Script Movie Database is a resource for tracking down screenplays for your favorite films. You may find that you want to go even deeper and learn about the world of screenwriting. If you’re a fan of podcasts, we’d recommend Scriptnotes hosted by John August, the screenwriter of Big Fish, Go, and Titan A.E. If you’re more of a bookworm, check out the classic guide Screenplay by Syd Field, who worked as a script reader in Hollywood and led workshops at the prestigious USC film school.

SOFTWARE FOR SCREENWRITING

You don’t need any special software for writing your screenplay. Paper and pencil, or Google Docs will work just fine. If you’re into using new tools and want to format your screenplay like a pro, we’d recommend WriterDuet. If you want to practice with the industry standard software Final Draft, you’ll have to fork over big bucks.

Pros:

It’s free and easy-to-use

Your projects will save to Google Drive

Cons:

It doesn’t offer any features specific to screenwriting

Pros:

There is a free version which allows you to work on 3 projects at a time

It is optimized for collaboration

Cons:

Many features are paywalled behind the paid tiers which range from $9.99-13.99 per month.

Pros:

It’s the industry standard

It’s a one-time purchase

Cons:

It costs $200+

BASICS OF SCRIPT FORMATTING

Again, you don’t need to worry about formatting your script in any official way, but if you’d like to practice using the grammar of screenwriting, here are the basics:

The basics of script formatting are as follows:

12-point Courier font size

1.5 inch margin on the left of the page

1 inch margin on the right of the page

1 inch on the of the top and bottom of the page

Each page should have approximately 55 lines

The dialogue block starts 2.5 inches from the left side of the page

Character names must have uppercase letters and be positioned starting 3.7 inches from the left side of the page

Page numbers are positioned in the top right corner with a 0.5 inch margin from the top of the page.

The first page shall not be numbered, and each number is followed by a period.

ADDITIONAL TIPS FOR WRITING SCREENPLAYS

There are so many resources online to get started with screenwriting, but we like this guide best from NYC Midnight, which hosts annual writing challenges in microfiction, flash fiction, short stories, and screenwriting. If you enjoy the No Budget Summer Film Workshop and love to write, you should definitely consider registering for one of NYC Midnight’s challenges

All text and examples ripped from NYC Midnight

Only write what the audience can see or hear

You are almost ready to begin your screenplay, but make sure you remember this tip when writing! If you are not describing what an audience can see or hear, it does not belong in a screenplay. For example:

Since the audience will not be able to see that Frank wished he had a time machine based on how it is written above, you will need to revise this so the audience can hear that he wished he had a time machine through a voice over (designated as V.O. for voiceover):

Now the audience will know that Frank wished he had a time machine through his voice over. Keeping this rule in mind when writing will make it very easy for the reader to visualize the film in their heads.

FADE IN

When beginning your screenplay, the first thing to write is FADE IN: to signify the screenplay is about to start. While it is considered a transition, it is only used once at the opening, and is 1.5" from the left margin as opposed to all other transitions in the screenplay which are approximately 6.0" from the left margin. You will need to double space between FADE IN: and the next line in your screenplay.

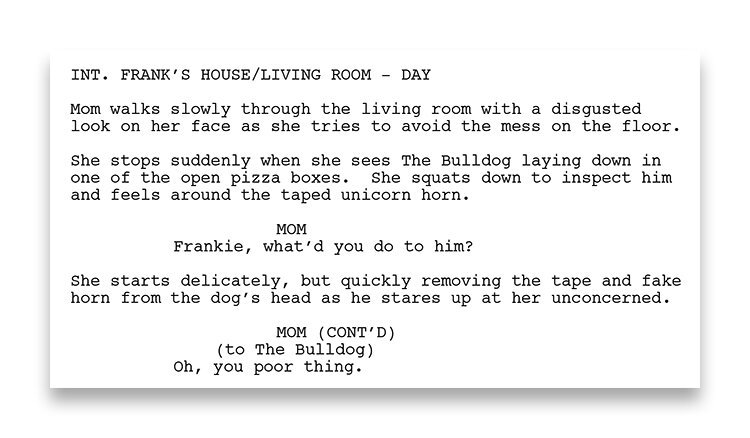

Scene headings

Each scene needs to have a scene heading which describes to the reader where and when it is taking place. Every time the location or time of day changes, a new scene heading is required. Scene headings are written in all CAPS. It includes three major elements:

Interior or Exterior

(Written as INT. or EXT.)

Defines if the location is inside or outside. For example, a restaurant would be considered an Interior location (INT.) and a public park would be considered an Exterior location (EXT.).

Location

(Written as MASTER SETTING/SPECIFIC SETTING)

Defines the location where the scene is taking place. It should define a master setting which is the main location such as a building, apartment, house, etc... and if necessary, any smaller, more specific locations within the master setting such as a kitchen, bathroom, living room, etc.. of a house (for example). A few examples of how the location is written are below:

INT. COFFIN

INT. POLICE STATION/HOLDING CELL

INT. FRANK'S HOUSE/LIVING ROOM

INT. FRANK'S HOUSE/BEDROOM

EXT. PUBLIC PARK

Time of Day

(Written as DAY or NIGHT)

The last element to include in a scene heading is the time of day. You don't need to include the exact time, just whether it's during the DAY or NIGHT. This helps during the pre-production process as filmmakers need to know if they will depend on natural light or will have any specific lighting needs.

So, using all the elements above, here are a few examples of complete scene headings:

INT. COFFIN - NIGHT

INT. POLICE STATION/HOLDING CELL - NIGHT

INT. FRANK'S HOUSE/LIVING ROOM - DAY

INT. FRANK'S HOUSE/BEDROOM - NIGHT

EXT. PUBLIC PARK - DAY

Scene headings are left justified at 1.5" from the left margin and require a double space before starting a new action line. Here is an example of a scene heading at the beginning of a screenplay:

ACTION LINES

This is where you create the images of the film in the reader's head. As stated above, action lines should only describe what an audience can see or hear. They should be short and concise, easy to visualize, and should move the characters, and plot forward. Action lines should always be written in the present tense.

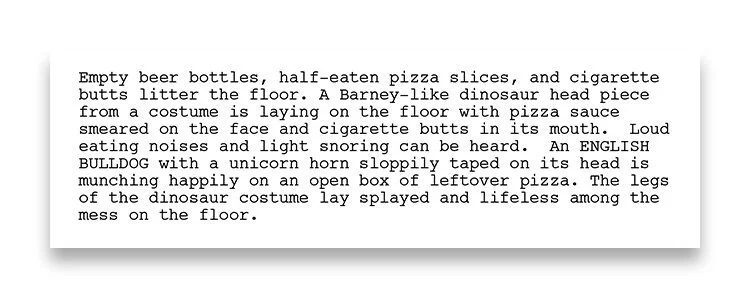

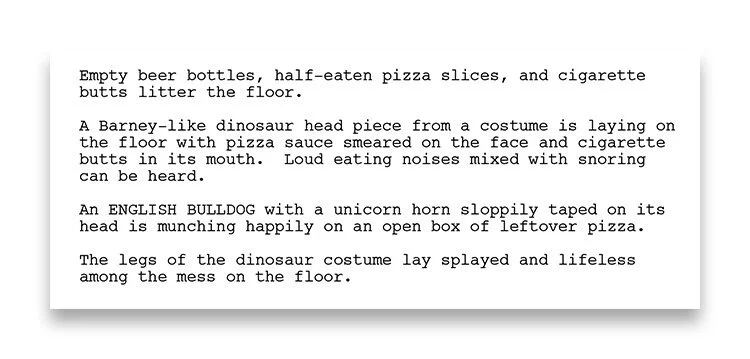

One Shot (or Action) per Paragraph

Typically, each shot or action requires it's own paragraph in a screenplay. Here is an example of how NOT to write an action paragraph:

This paragraph is way too clunky and includes several shots which should have their own paragraph. Below is a better way to pace it out:

You'll see that now each paragraph represents a shot and flows much easier for the reader. When describing the shot or introducing a character through your action lines, try not to exceed 4 action lines per paragraph for the sake of the reader. This rule varies slightly, but most are in agreement that the shorter the better.

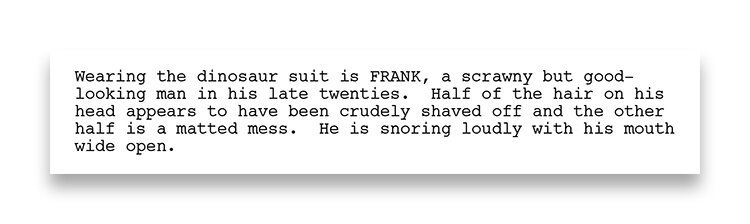

Characters are also introduced through action lines. Always put a character's name in ALL CAPS when introducing them for the first time in your screenplay. You don't need to keep them in caps throughout the screenplay, only the first time you introduce them to the reader. Animals, such as the ENGLISH BULLDOG above, need to be capitalized as well when first being introduced.

It's also important to briefly describe the character in the introduction so that it paints a better picture for the reader. What age range? Do they have important physical attributes that help define their character? A few examples of important attributes would be eyeglasses, a large scar on their face, morbidly obese, scrawny, in a wheelchair, tattoos, very carefully manicured, etc. Are they wearing something in particular that helps define their character such as a tuxedo or flip flops? An example of a character introduction is below:

character introductions in ACTION LINES

Character descriptions are not necessary for minor characters if they don't add to the story. For example, a MALE SECURITY GUARD that makes an appearance in a single shot does not need 3 lines of description for his character unless it's vital to the story.

When introducing minor characters, such as the MALE SECURITY GUARD above, make sure to include #1, #2, and so on if you are using more than one of the same character. For example, if you will introduce another MALE SECURITY GUARD at a later time in the screenplay, make sure to refer to the first as MALE SECURITY GUARD #1 when you introduce them and continue to use that name throughout the screenplay.

character descriptions in action lines

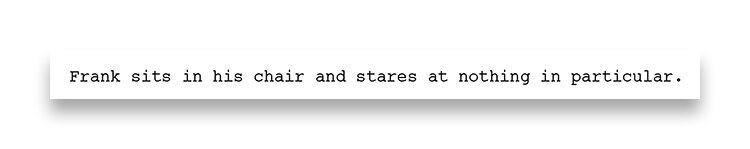

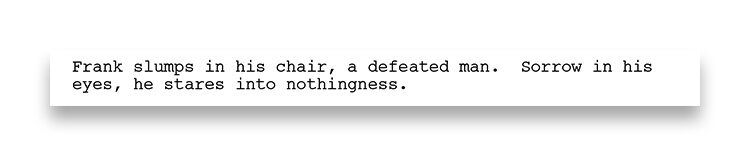

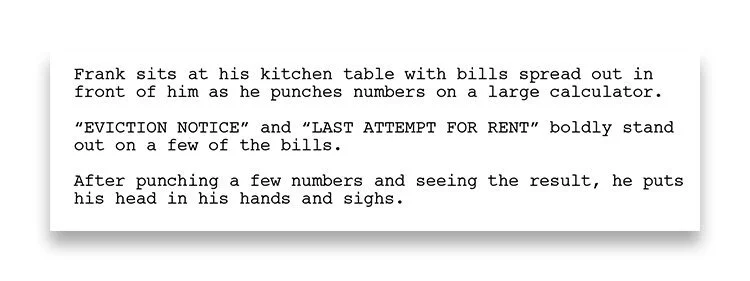

Once you have introduced the characters, you don't need to continue to include their physical attributes unless it's important to the scene. But, it is important to convey the character's emotional state in most scenes so the reader sees his or her development throughout the story. The better you can describe the character's emotional state, the more the reader will be able to visualize it and get invested in the story. For example:

This description explains the scene but doesn't do a very good job of describing his emotional state. Here is a better description of his emotion:

Of course, there are infinite number of ways a writer can convey the story through their action descriptions, but remember that getting the reader caught up in the story through the emotion of the characters and descriptions of the scene is one of the most important aspects of screenwriting.

show, don’t tell

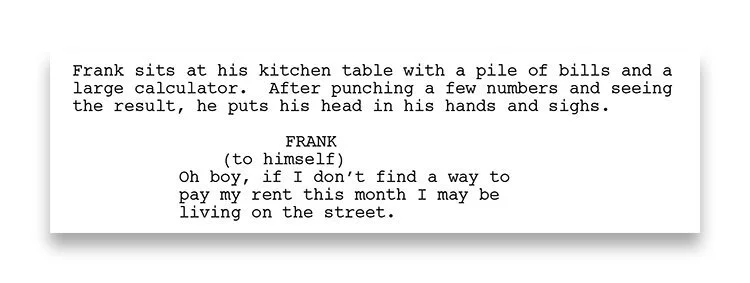

An age old adage in screenwriting (and creative writing for that matter) is that it is usually always better to communicate something through an image or images, rather than having a character explain it to the audience. Of course dialogue is necessary in most stories, but following this rule when possible will make for a more visual read and a more watchable film. For example:

While the writer is trying to get across to the audience that Frank is in debt and in a big predicament if he doesn't pay his rent, this isn't the best way to do it. It's not realistic for the character to be talking to himself about something that he already knows and will take most people out of the story immediately.

Don't underestimate your audience. By simply flashing an EVICTION NOTICE or LAST ATTEMPT FOR RENT letter lying next to his calculator in an action line (shown below), the audience immediately grasps that he is in deep financial trouble without having your character say a word.

DIALOGUE

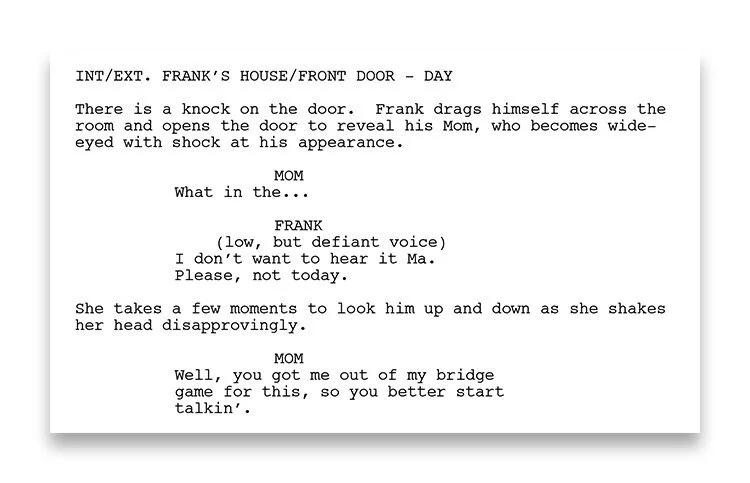

When your characters speak, it is called dialogue and it is written in a specific way. First, you need to write the name of the character speaking in ALL CAPS approximately 3.5" from the left margin. Any Parentheticals (further described in the section below) are single spaced beneath the speaking character approximately 3.0" from the left margin. The dialogue is then inserted as a single space below approximately 2.5" from the left margin. Never center the dialogue on the page! It should always be left justified at the approximate margins listed above.

If there is more than one character speaking in the scene, you will need to identify each speaking character every time they speak. Speaking characters are double spaced. For example:

If the same character speaks through an action, you need to write (CONT'D) next to the character's name after the line of action. For example:

This is to let the filmmakers know that the speaking continues through the action and will most likely end up as one shot as opposed to several shots. As with most of the basics such as margins and spacing, CONT'D is taken care of automatically by most screenwriting programs.

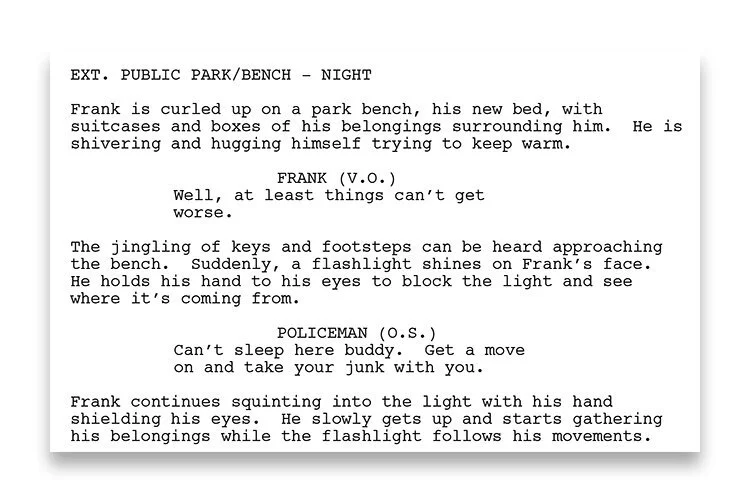

voiceover and off-screen

When a character is speaking in a scene but is not physically in the scene or not physically speaking in the scene, you need to designate the dialogue as either voice-over (V.O.) or off-screen (O.S.) which is placed on the same line as the speaking character's name in the dialogue.

If the character is physically present in the scene but is not visible during their dialogue (i.e. locked in the bathroom, hiding under the bed, etc..) then it needs to be designated as off-screen (O.S). If they are not physically present, such as acting as a narrator or speaking on the phone, then it should be designated as a voice-over (V.O.). Also, if the actor can be physically seen but you wish to have him/her communicating their thoughts or narrating to the audience without actually speaking in the scene, you will need to designate the dialoge as voice-over also (V.O.).

PARENTHETICALS

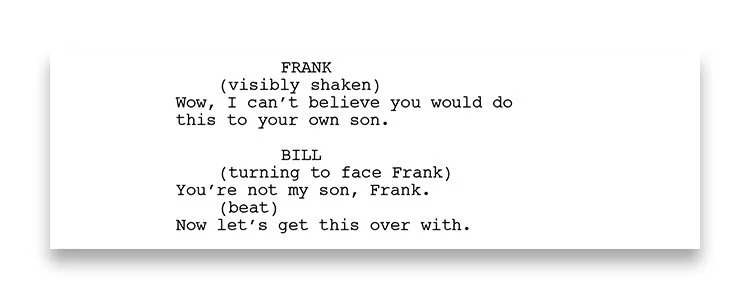

Parentheticals are direction for the actors and are placed beneath the speaking character's name in the dialogue to express the actor's emotions or actions. As with any direction in a spec script, it should be minimal, so make sure to use parentheticals only when necessary.

Parentheticals are placed on their own line, in parenthesis (), single spaced below the speaking character's name, and approximately 3.0" from the left margin. They are typically only a few words, never a full sentence, and always in lower case. If you are using more than a few words to describe the emotion or action of the actor, you should be using an action line preceding the dialogue.

When you need to represent a brief pause in the character's speech, you should use the parenthetical (beat) between the lines of dialogue.

Some examples of parentheticals using emotion, action, and a brief pause are below:

TRANSITIONS

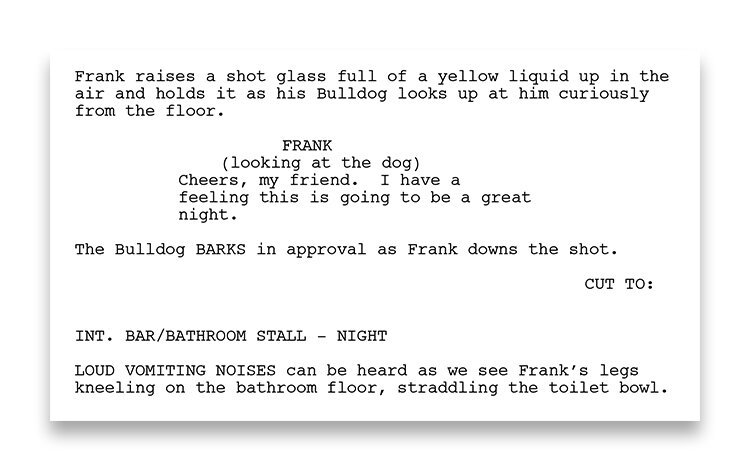

Direction for how one shot transitions in the next shot in your screenplay is called a transition. For example, "FADE IN:", the very first text in a screenplay, represents the very first shot of the film fading in from black (or another color). All transitions are double spaced and are approximately 6.0" from the left margin.

Popular transitions also include "DISSOLVE TO:" and "CUT TO:", even though "CUT TO:" is redundant since every shot cuts to another shot. "CUT TO:" is most commonly used for comedic or dramatic effect by alerting the reader to the contrast between the shots. For example:

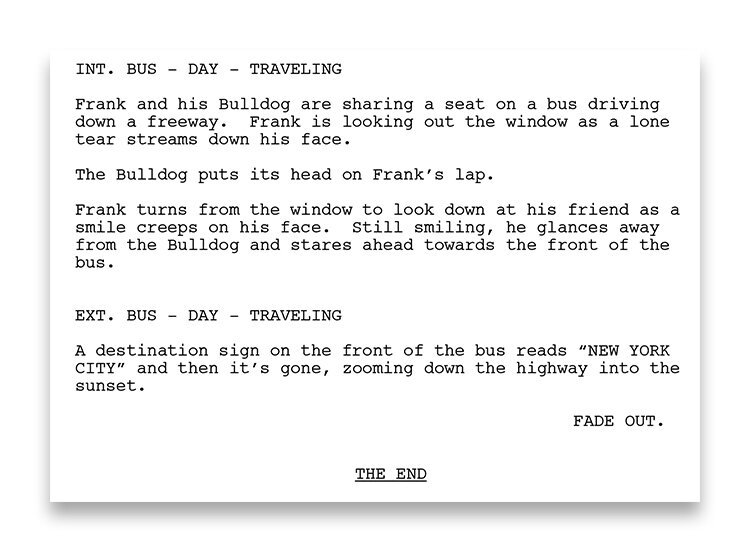

The other important transition besides "FADE IN:" that needs to be included in your screenplay is "FADE OUT.", which represents the end of the film. There should be no further text beyond "FADE OUT." besides "THE END" which is double spaced and centered on the page. "THE END" is not necessary though, since "FADE OUT" designates the end of the screenplay as well. An example is below: